In 2011, Lucy Zhang, Ben Davenport and Jon Perlow joined Facebook and started building the Facebook messenger. A major hurdle in their endeavor was long latency when sending a message. The method that they were using to send messages was reliable but slow. They were also able to optimize it to a certain extent. A few weeks before the launch, they explored the Messaging Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) protocol. With the help of MQTT, Lucy Zhang and team were able to establish and maintain a persistent connection with the Facebook servers without reducing the battery life.

So, what is MQTT protocol?Created in 1999 by Dr. Andy Stanford-Clark of IBM and Arlen Nipper of Arcom, MQTT is a lightweight messaging protocol on top of TCP/IP protocol. MQTT is designed for constrained devices (devices with low memory and network bandwidth) and wireless networks with varying levels of latency due to unreliable connection.

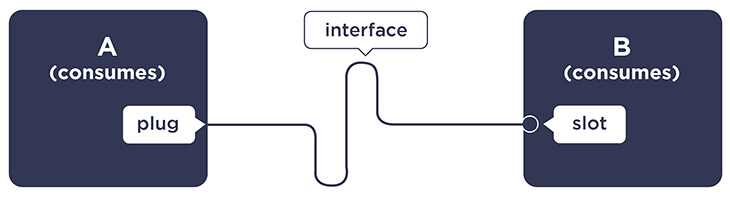

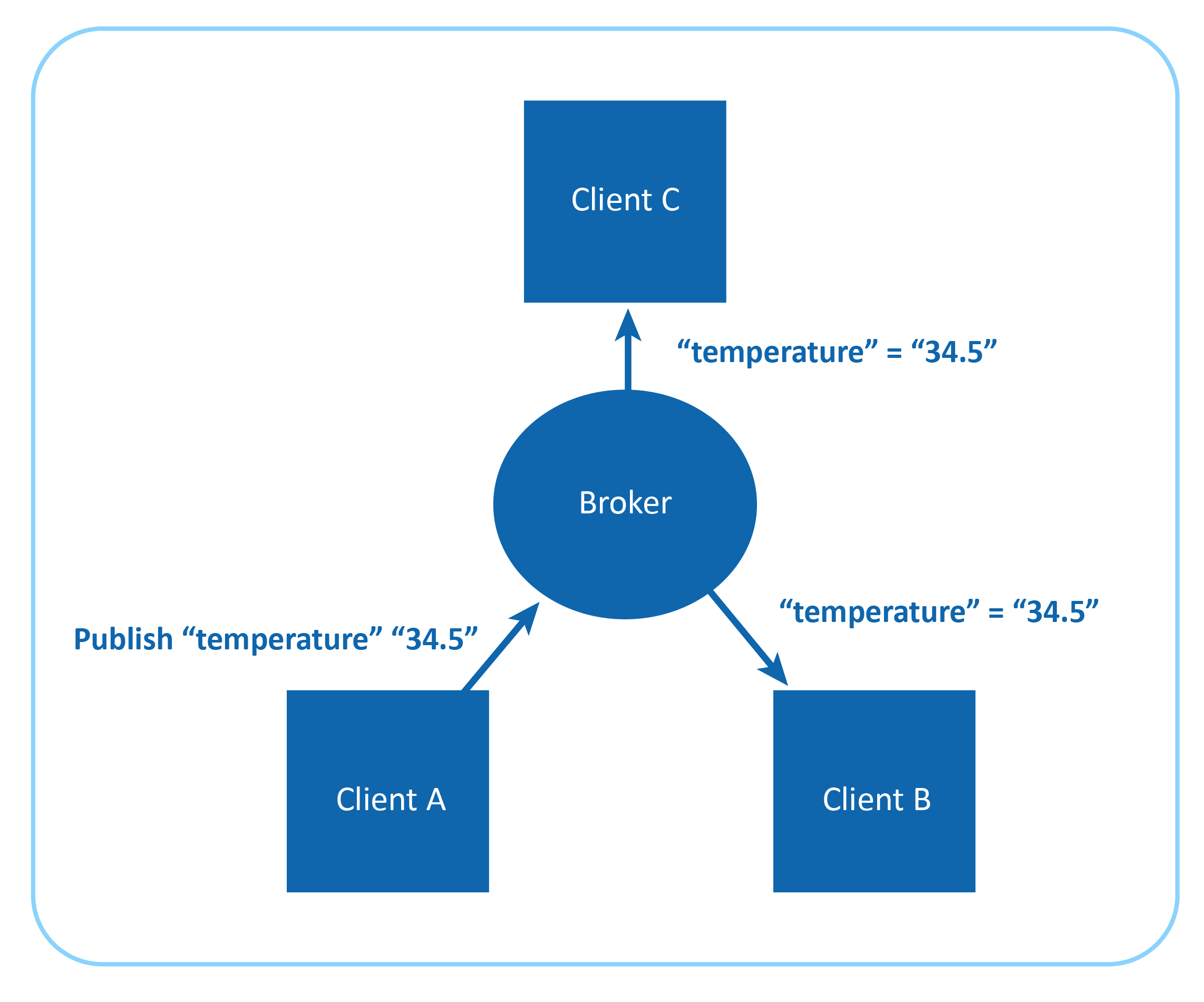

MQTT protocol is a client-server, publisher/subscriber, open, and light-weight messaging transport protocol. At the heart of MQTT is the central communication point known as MQTT broker. It is responsible for dispersing messages to rightful clients.

Each client which publishes a message to the MQTT broker includes the routing information, known as topic. Clients may subscribe to multiple topics and broker all the messages published matching the topic. The clients don't have to know each other to receive information; they just have to subscribe to relevant topics.

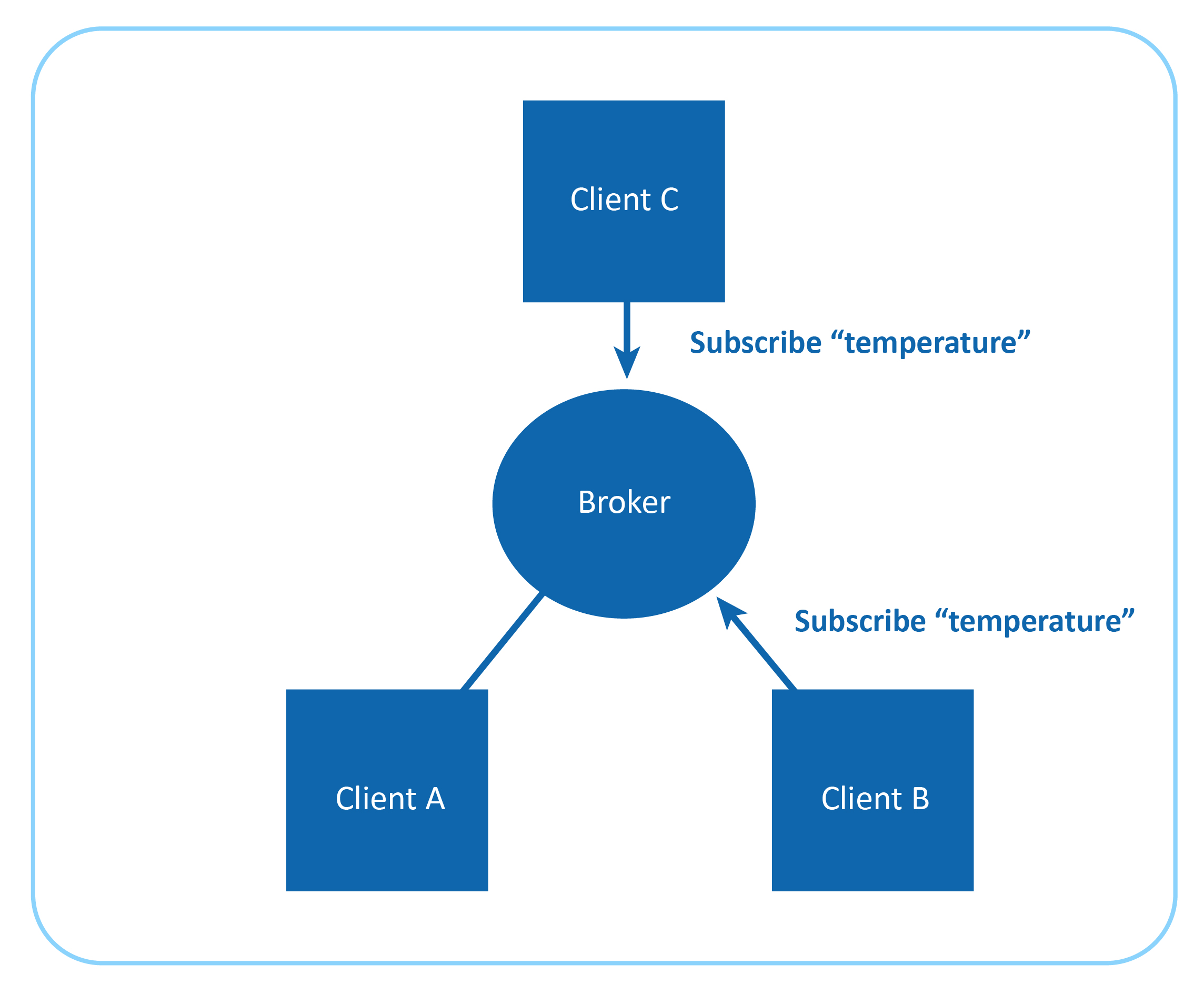

For instance, imagine a simple network of three clients, i.e A, B and C, where each is connected to a broker via a TCP connection. Client-B and Client-C subscribe to topic: temperature.

Client-A publishes 34.5 for topic temperature. The broker identifies this and forwards this message to all the subscribers, which in this case are Client-B and Client-C.

The publisher-subscriber architecture of MQTT makes it a highly scalable solution, without creating dependencies between data producers and consumers.

Message format of MQTT protocol

All the messages of MQTT have a small code footprint, hence it is popular as a lightweight messaging protocol. Each MQTT message consists of the following:

- Fixed header (2 bytes)

- Optional variable header

- Message payload (<= 256MB)

- Quality of Service (QoS) level

MQTT supports one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many communication.

By lowering the amount of data transmitted, MQTT makes itself a perfect protocol for constrained IoT devices.

Message payloads are encoded in binary. In an open network where the recipient is from a different manufacturer will face issues decoding it as there is no information of how message payload is encoded.

Quality of Service (QoS) level for MQTT protocol

The quality of service levels determines how the content is managed. MQTT uses three different QoS levels. It is important to choose the right QoS level for every message because it determines how the client and server communicate to deliver the message. The QoS levels of MQTT are as follows:

- QoS 0 : Messages delivered per the best efforts of the operating environment, but message loss can occur

- QoS 1 : Messages delivery assured but duplicates can be created

- QoS 2 : Message to deliver exactly once

MQTT provides us with an option to set the appropriate QoS level, but remember, higher the QoS, lower the performance.

Security of MQTT protocol

MQTT allows you to pass username and password as an MQTT packet. Encryption of a message across the network can be handled independently of MQTT with Secure Sockets Layer (SSL). It has a minimal authentication feature built in. Username and password are sent as clear text. To make it secure, Secure Sockets Layer (SSL)/ Transport Layer Security (TLS) must be employed, but SSL/TLS is not a lightweight protocol.

Many industry experts believe MQTT will play a major role in IoT by contributing to fields such as inventory tracking, and medical IoT..