Humans can easily detect and identify objects present in an image. The human visual system is fast and accurate and can perform complex tasks like identifying multiple objects and detect obstacles with little conscious thought. With the availability of large amounts of data, faster GPUs, and better algorithms, we can now easily train computers to detect and classify multiple objects within an image with high accuracy. In this blog, we will explore terms such as object detection, object localization, loss function for object detection and localization, and finally explore an object detection algorithm known as “You only look once” (YOLO).

Object Localization

An image classification or image recognition model simply detect the probability of an object in an image. In contrast to this, object localization refers to identifying the location of an object in the image. An object localization algorithm will output the coordinates of the location of an object with respect to the image. In computer vision, the most popular way to localize an object in an image is to represent its location with the help of bounding boxes. Fig. 1 shows an example of a bounding box.

A bounding box can be initialized using the following parameters:

- bx, by : coordinates of the center of the bounding box

- bw : width of the bounding box w.r.t the image width

- bh : height of the bounding box w.r.t the image height

Defining the target variable

The target variable for a multi-class image classification problem is defined as:

Loss Function

Since we have defined both the target variable and the loss function, we can now use neural networks to both classify and localize objects.

Object Detection

An approach to building an object detection is to first build a classifier that can classify closely cropped images of an object. Fig 2. shows an example of such a model, where a model is trained on a dataset of closely cropped images of a car and the model predicts the probability of an image being a car.

Now, we can use this model to detect cars using a sliding window mechanism. In a sliding window mechanism, we use a sliding window (similar to the one used in convolutional networks) and crop a part of the image in each slide. The size of the crop is the same as the size of the sliding window. Each cropped image is then passed to a ConvNet model (similar to the one shown in Fig 2.), which in turn predicts the probability of the cropped image is a car.

After running the sliding window through the whole image, we resize the sliding window and run it again over the image again. We repeat this process multiple times. Since we crop through a number of images and pass it through the ConvNet, this approach is both computationally expensive and time-consuming, making the whole process really slow. Convolutional implementation of the sliding window helps resolve this problem.

Convolutional implementation of sliding windows

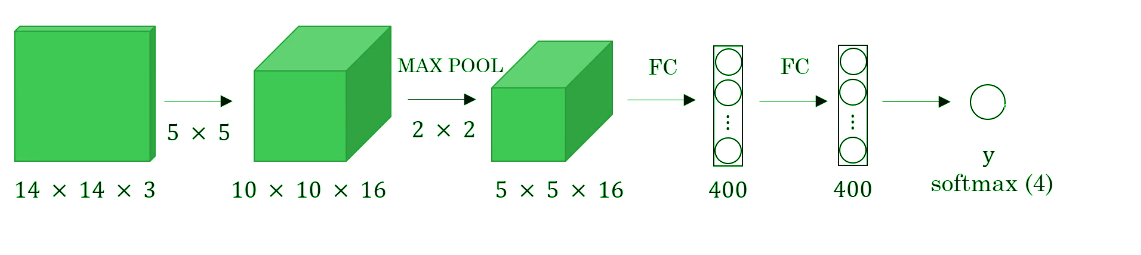

Before we discuss the implementation of the sliding window using convents, let’s analyze how we can convert the fully connected layers of the network into convolutional layers. Fig. 4 shows a simple convolutional network with two fully connected layers each of shape (400, ).

A fully connected layer can be converted to a convolutional layer with the help of a 1D convolutional layer. The width and height of this layer are equal to one and the number of filters are equal to the shape of the fully connected layer. An example of this is shown in Fig 5.

We can apply this concept of conversion of a fully connected layer into a convolutional layer to the model by replacing the fully connected layer with a 1-D convolutional layer. The number of the filters of the 1D convolutional layer is equal to the shape of the fully connected layer. This representation is shown in Fig 6. Also, the output softmax layer is also a convolutional layer of shape (1, 1, 4), where 4 is the number of classes to predict.

Now, let’s extend the above approach to implement a convolutional version of sliding window. First, let’s consider the ConvNet that we have trained to be in the following representation (no fully connected layers).

Let’s assume the size of the input image to be 16× 16× 3. If we’re to use a sliding window approach, then we would have passed this image to the above ConvNet four times, where each time the sliding window crops a part of the input image of size 14× 14× 3 and pass it through the ConvNet. But instead of this, we feed the full image (with shape 16× 16 × 3) directly into the trained ConvNet (see Fig. 7). This results in an output matrix of shape 2 × 2 × 4. Each cell in the output matrix represents the result of a possible crop and the classified value of the cropped image. For example, the left cell of the output (the green one) in Fig. 7 represents the result of the first sliding window. The other cells represent the results of the remaining sliding window operations.

Note that the stride of the sliding window is decided by the number of filters used in the Max Pool layer. In the example above, the Max Pool layer has two filters, and as a result, the sliding window moves with a stride of two resulting in four possible outputs. The main advantage of using this technique is that the sliding window runs and computes all values simultaneously. Consequently, this technique is really fast. Although a weakness of this technique is that the position of the bounding boxes is not very accurate.

The YOLO (You Only Look Once) Algorithm

A better algorithm that tackles the issue of predicting accurate bounding boxes while using the convolutional sliding window technique is the YOLO algorithm. YOLO stands for you only look once and was developed in 2015 by Joseph Redmon, Santosh Divvala, Ross Girshick, and Ali Farhadi. It’s popular because it achieves high accuracy while running in real time. This algorithm is called so because it requires only one forward propagation pass through the network to make the predictions.

The algorithm divides the image into grids and runs the image classification and localization algorithm (discussed under object localization) on each of the grid cells. For example, we have an input image of size 256 × 256. We place a 3× 3 grid on the image (see Fig. 8).

Next, we apply the image classification and localization algorithm on each grid cell. For each grid cell, the target variable is defined as

Do everything once with the convolution sliding window. Since the shape of the target variable for each grid cell is 1 × 9 and there are 9 (3 × 3) grid cells, the final output of the model will be:

The advantages of the YOLO algorithm is that it is very fast and predicts much more accurate bounding boxes. Also, in practice to get more accurate predictions, we use a much finer grid, say 19 × 19, in which case the target output is of the shape 19 × 19 × 9.

Conclusion

With this, we come to the end of the introduction to object detection. We now have a better understanding of how we can localize objects while classifying them in an image. We also learned to combine the concept of classification and localization with the convolutional implementation of the sliding window to build an object detection system. In the next blog, we will go deeper into the YOLO algorithm, loss function used, and implement some ideas that make the YOLO algorithm better. Also, we will learn to implement the YOLO algorithm in real time.

Have anything to say? Feel free to comment below for any questions, suggestions, and discussions related to this article. Till then, keep hacking with HackerEarth.